| Home > Floripedia > Emily Holder | |

Emily Holder

At the Dry Tortugas During the War1892

The following is an account written by Emily Holder describing her memories of Fort Jefferson. As the wife of the post surgeon during the turbulent 1860s, she led a very singular life on one of the most out-of-the-way places then imaginable. As the congenial wife of a prominent member of the fort's garrison (and one of the few women on the island), she had broad access to many areas around the fort. Beginning in January 1892, her journal was published in a series of installments of The Californian Illustrated. Reproduced here, they tell the poignant and often fascinating story of the hardships, isolation and drama of daily life at the Dry Tortugas in the nineteenth-century.

The great progress in modern scientific warfare within the last quarter of a century has made fort-building to our Engineer Corps a difficult problem. Discoveries in destructive power so keep pace with those of resistance that for humanity's sake we can but hope that the time may not be far distant when "They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning-hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore," and that just and righteous arbitration will be method of tranquilizing all national disturbances.

Among our coast defenses thirty-five or forty years ago Key West and Tortugas, Florida, were considered stations of sufficient importance for the establishment of elaborate fortifications.

They were the extreme points reaching out toward the Spanish possessions. In any case they would be useful as depots of supply for our navy; and a fort on one of these keys farthest from the mainland would prevent its occupation by a foreign force.

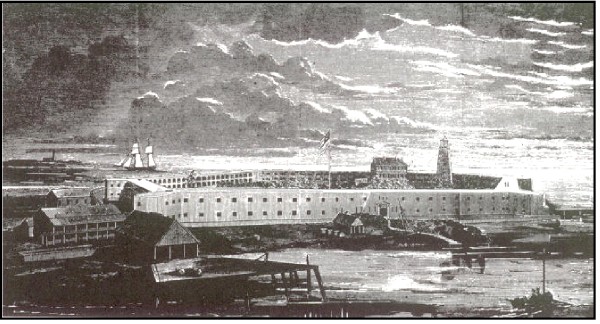

About the year 1847 Fort Jefferson was commenced under the charge of Captain Wright of the United States Engineer Corps, and in 1859 had assumed a formidable appearance as it rose, apparently, directly from the sea to a height of nearly sixty feet, and after the towers at each bastion were completed presented a castellated and picturesque appearance.

This great work gave employment to some two or three hundred workmen, mostly slaves, whose masters lived in Key West, sixty miles away. So large a force naturally necessitated a resident physician. Doctor Whitehurst, who held the appointment for several years, resigned in the summer of this year.

Professor Agassiz had visited Tortugas the preceding winter, returning very enthusiastic over the coral and other marine forms; and those in authority had consented that the succeeding physician should be chosen with reference to biological science.

Professor Baird of the Smithsonian Institution knowing all this and also that my husband combined both qualities of surgeon and naturalist, it was through this influence that the position was tendered him and accepted in the autumn of 1859.

It seems strange to refer to letters that say the trip from New York to Washington was the most tiresome part of the journey, taking from six o'clock at night until six the next morning, with so many changes that the attempt to sleep was only an aggravation-when now the comforts and luxury in traveling simply depend upon the length of one's purse.

From there to Charleston the trip was slow but sure,-literally for the accommodation of every one. I remember the train stopping one day in the woods without any apparent cause. After a while people began to question the reason of the delay, when an old couple were seen coming through the woods putting on their wraps as they came. When they were assisted aboard, the train started on as leisurely as though time was of little value; we had evidently left hurry and bustle behind.

While in Charleston, although it impressed as having a general air of dilapidation,-its moldy walls, uneven sidewalks, and a want of thrift even in the better part of the city,-yet with it all we felt that the people found more enjoyment in life than we in the North with all our hurry and energy.

Taking the Isabel, the Havana steamer, we reached Key West in the evening a few days later, finding the mail schooner Tortugas waiting to convey us to Fort Jefferson, or Tortugas; so we saw nothing of the town, only as we steamed into the wharf; yet it gave us a most pleasant impression,-the lights glimmering through the cocoanut trees, the white sand, glimpses of the houses half hidden in the foliage, and the brilliant moonlight throwing a fairy-like glamor over all, making a picture never to be forgotten.

One night took us to Fort Jefferson, that in time became known as the famous Dry Tortugas; and our fist view in the early morning as we sailed in through the winding channel was surely suggestive of a prison. Over the top of the fort we caught sight of trees and the roof of a building with a tall, white lighthouse towering over all. The little keys that we had passed, some pure white, others with a few trees and shrubs, took away something of the isolated feeling.

Three miles away stretched out the largest of all these islands except the one on which the fort was built, on which was another larger lighthouse. The exterior of the fort was bare and repulsive, the interior offering a decided contrast.

Here were trees of the deep green belonging to tropical vegetation, so restful to the eye in the glaring sun; and as the walls inclosed about thirteen acres, and water could not be seen, I instinctively lost the feeling of being so far from the mainland.

The walk, hard as cement and white as snow, partly shaded by the evergreen trees, led past the lighthouse and cottage of the keeper to the opposite side of the fort, where we were taken into a large, cool and pleasant house, and given a warm welcome by Captain Woodbury and his charming wife and family, who soon made us feel that a home does not depend upon locality, but in the hearts of the people.

It had been very difficult in our hurried departure from home to learn just what was necessary for living in such an out-of-the-way place; and, as we only looked forward to a stay of one winter, we took nothing for housekeeping purposes, thinking that we should probably board at some hotel perhaps-suggestive of the idea we had of the Dry Tortugas.

We soon concluded that, however primitive it might be, a home of our own would be preferable, so went shopping at the one store outside the walls. The winds had blown up sand until there was an acre perhaps stretched along the moat outside the seawall; and on this atom of land was the store, mess-hall for the workmen, carpenter-shop and a long building where the men slept, and further along the edge of the sand stood the Engineer Hospital, where it was always cool and breezy.

The store was for the accommodation of the men, and contained a medley of things. Here we bought a stove and enough of the necessities to start our primitive housekeeping.

We had some tables made by the island carpenter, a bedstead, also a rocking-chair, that must be in existence now judging from its strength and durability. There was always a mystery about its rocking power, which my kindly feeling for the carpenter prevented questioning. It was not a frisky piece of furniture that made one feel in danger of tipping over, but tall, staid and dignified, requiring some effort to tilt it. The length of the rockers suggested the long swing of a hammock, so that one started off with anticipation of a restful enjoyment; but these anticipations were soon dispelled by its little tilt forward and very sudden termination of the backward swing, causing the occupant to look around for the obstruction, when, seeing nothing, the impetus would be given again with a little more energy. After several such unsuccessful attempts we came to the conclusion that it was its own peculiar way of rocking; and the mystery was never solved why such a wonderful length of rockers produced so few rocks; but we managed to obtained unqualified comfort from it, and some quiet amusement when strangers attempted it.

We finally began housekeeping with an old colored woman as cook and a boy as waiter. The former was a character, a slave of a Mrs. Fogarty, who kept the mess-hall and who loaned her to me until my cook, a certain Aunt Rachel, could come from her master at Key West.

The latter was evidently held in great veneration by the colored people; and I was considered very fortunate in securing her. She was a famous cook and the wife of Bill King, the cook of the schooner Tortugas.

Aunt Eliza was so black that in the dark I could see nothing but the whites of her eyes, under a huge yellow turban from which two little black braids the size of pipestems stood at right angles behind each ear, from which hung enormous gilt hoops. Her front teeth had long since disappeared; and I found that the strong odor of a pipe, which, she said, came from Jack's smoking in the kitchen, was from her own, which I found in all sorts of improper and inconceivable places.

She stooped so that I asked her the cause when she replied: 'Why, honey, dat's from workin' in de cotton field. I'se so ugly dey couldn't keep me in de house; and after Mr. Phillips (the overseer) bought my gal Clarssy I dun took on so, and was dat bad, my master glad nuf to sell me down yer."

But I said where was your husband? "Oh, I lef him and got Jack." Jack was a good-looking colored boy about thirty, while she confessed to fifty. He was one of the workmen owned in Key West, and lived with Aunt Eliza over our kitchen, which was a separate house with a chamber over in the rear of the larger one. She showed none of her ugliness to me, but one day I heard on outcry and ran to the dining-room window just in time to see Jack flying out of the back gate, with Aunt Eliza in close pursuit swinging an axe, threatening to "split his head open if he ever came there again."

I called her in to remonstrate, and at first she said she really meant it, but after awhile confessed she did it to frighten him, as he was so lazy he would not wait upon her. "I'se boss, Missus," was her explanation.

For several days she had supreme control of the kitchen, with little Lewis, and smoked her pipe in peace; then she asked me if Jack might come back; she was lonesome. I consented upon the condition that if there were any more disturbances he must stay away entirely.

She evidently wanted to please, and was anxious to remain in my service; yet without being openly disloyal to Aunt Rachel, she never lost an opportunity to give a good reason for her delay in coming.

The fort on the inside showed long stretches on each curtain of arches, making pleasant places for walking, cool and shady; and in the moonlight the effect was really beautiful. Looking not unlike some grand old ruin with its lights and shadows, one could invest it with all sorts of romance. Cooper laid the scene of "Jack Tier" here, in a cottage by the lighthouse which had given place to the one now standing.

The seawall around the moat was our favorite walk, making nearly a mile. The atmosphere was so clear that the space between the sky and the earth seemed interminable. The sun was dazzling in its brightness.

The wind coming in through the embrasures kept the shiny leaves of the mangrove constantly quivering; and the rattling among the cocoanut branches sounded not unlike gentle rain. Outside the deep blue water was covered with whitecaps, which broke into waves wherever the coral approached the surface.

Such was our winter weather, except when a norther came scurrying over the gulf; then, as the children say, we played that it was cold, and built a fire in one of the big fireplaces, listened to the wind blowing the sand against the windows, and said, "Doesn't that sound like snow?"

The northers lasted three or four days; then we would have another two or three weeks of lovely summer days again, and my husband would spend part of each day collecting specimens. He had built on the water's edge a little house with a wall extending fifteen feet square out into the water, so that it flowed in and out through the interstices; and here he kept all kinds of specimens and watched their growth and development.

It was most interesting even to those who did not claim to be naturalists; and, as all our outside pleasures were necessarily aquatic, one learned without an effort from the familiarity of natural objects; and as our resources were necessarily limited we took advantage of everything that presented itself, and so found amusement and entertainment.

On Sundays Captain Woodbury; who with his family were Episcopalians, read the lessons and afterwards a sermon. Mrs. Woodbury had organized a choir, some among the white workmen, in fact any one who could sing; and everybody was invited to attend the service; oftentimes filling the large parlor.

Rowing and trips to the adjacent keys for shells, especially after a norther, were our frequent pastimes.

The water was so clear we could distinguish objects clearly at the depths of sixty feet; and it was like rowing over a garden when it was calm, to drift along watching the fish darting in and out among the huge heads of coral, and sea-fans that gently waved back and forth in the current.

Often there would be large schools of harmless sharks close in shore. As there were acres of shoal water only a few feet deep, where all this could be seen, and as there were always boats ready we went rowing or sailing as the people on the mainland went to drive.

The event of this first winter was a visit to Key West, which, in its palmiest days, was a lovely place with charming society, though the war cloud changed it utterly and hopelessly later on.

We arrived at night, going to the hotel, but before breakfast the next morning, Captain Curtis, to whom we had letters of introduction, came and took us to his lovely home sheltered in a grove of cocoanut trees. It seemed a bit of fairy land, so purely tropical was it with all the luxury and taste of a Northern home. I shall never forget the first impression it made upon me.

We were given the quaintest, cosiest little house they called the cabin to sleep in; it was in the yard, embowered in trees and flowering shrubs, and was really a ship's cabin taken from a wreck, brought there and arranged as a guest-room, or two rooms rather, and a dressing room, with a little piazza in front. The very romance of the surroundings kept me awake listening to the gentle sound of the wind among the trees, when to add to all this we were suddenly roused by a serenade of stringed instruments, sweet and soft, carrying out the fairy idea of it all.

The next day we dined at Fort Taylor, meeting Captain Hunt and Professor Trowbridge. The former was the engineer in charge,--a most agreeable gentleman, full of life and good humor. His wife, who after his sad death became the famous author "H.H.," was in the North. I remember Captain Hunt took us to ride in a huge carriage drawn by a very small mule that was wise enough to understand that, when the whip dropped through the drawbridge, he was master of the situation; and nothing short of the prods of the Captain's umbrella, after a cane had been sacrificed, would arouse him to a sense of duty; but he carried us safely to all the points of interest.

The following night a party was given us at the fort, where we met many delightful people,-Judge Marvin, Judge Douglass, the officers of the steamship Corwin, and a number who were to leave the next day; and as Captain Hunt was to return with us on a visit at Captain Woodbury's, and Judge Douglass and Professor Trowbridge were going to Havana, we were invited to go down on the steamer Corwin with them.

My memories of Key West, as it was then, are delightful, standing out clear and bright; every one was happy and contented in their island home.

So many names come into my mind as I write;-Mr. Herrick, the rector and his hospitable wife, the Bethels, the Browns, who had the most beautiful house on the island, and many others who showed us many kinds of attentions.

Judge Douglass was an inimitable story-teller; and it was a merry party that reluctantly separated at eleven, when the steamer reached the entrance of Tortugas harbor on the return, sending us ashore in a cutter in charge of an officer, a son of Bishop Odenhemier of New Jersey.

Captain Hunt remained a week, and Mrs. Woodbury gave a dinner party for him; and, finally, two days before he left, I extended the same hospitality, wondering if he would notice the similarity in china and table equipment, for our "things" were yet en route; even the chairs had not reached Key West.

Calling in Sophy Benners, the chief cook of the island, who belonged to the lighthouse keeper, and deposing old Eliza, who looked rather mournful over the downfall, we planned a dinner that must have been a surprise; there were fruits and flowers and borrowed china, even to the chairs, which I feared encountered the guests going into the back door as they entered the front, as the hall passed through from front to rear.

My guests were kind enough to pronounce the dinner a success, and I enjoyed the novelty of the whole thing extremely, perhaps more than I should if my ingenuity had been less taxed.

A few days later Sophy Benners (for the slaves all took the name of their masters) and Peter Philor proposed entering the married state with more than ordinary pomp and splendor. The master, Mr. Philor, lived in Key West, owning a large number of slaves who worked on the fort, there being four Johns alone, the last one always giving his name as "John de fofe, sah" in answer to the overseer's call.

Peter had obtained permission from his master to marry Sophy, and so came to Captain Woodbury to ask if he would marry them. The latter replied, "Certainly, where are you going to be married?"

"In your parlor, sah.," said Peter. And we heard that Sophy had given out invitations to this effect:

"Sophy will be agreeable to her friends at seben o'clock in Captain Woodbury's parlor; after dat comes de ball."

Aunt Eliza soon came up to tell me what was going to happen, and I asked her if she was going to the ball.

"Sartinly, ma'am, and I must go and wash my skin, now I'se got de kettle on."

The wedding was affair to be remembered. All the white people assembeled in the front parlor; and at the supreme moment the folding doors were thrown open, and the bridal party came forward: two bridesmaids all in white, and two groomsmen. The bride wore a white veil with flowers; and she married with a ring, her mistress giving her away (in theory only).

The boys (all black men were called boys) had had their hair braided for a week; and some of their heads were large enough to fill a bushel basket.

After the couple were pronounced man and wife they adjourned to the mess-hall, the guests following in about an hour, as every one had been formally invited.

We saw them dance a while; then they passed us cake and wine, and we started to go home, when some one said we ought to stay and see Aunt Eliza dance a jig; and to my amazement my old cook with a young man took the floor. She looked rather shy, saying, "de Lor', I cyant dance;" but the music soon took possession of her poor old feet, and she gradually straightened up, swaying back and forth with the music, evidently forgetting everything else. She danced away I could scarcely believe that the jubilant figure was the old slave that groaned and grumbled about the little work demanded of her. She outdanced the boy and left him far behind. They are as a race music-loving; and I saw in a dark corner of the ballroom my incorrigible servant Lewis dancing all by himself happy as a king.

We learned that the colored people knew old Eliza's gift and had coaxed her to come and dance a jig, with the promise that one of the boys should do all her scrubbing on Friday; and we certainly came near being flooded the following day. He was as good as his word, as the house shone from top to bottom.

Old Eliza was such a character I cannot refrain from recounting some of her amusing, yet at the same time rather perplexing, acts.

The dignity of the cook was not easily adjusted, and rather overpowering, but she improved as time went on. In the early days of her new position, installed in a house the same as the cook of the commanding officer, she felt her importance and showed it, not unlike wiser and older people. Such differences vary only in degree; and in her case it was very amusing.

Fresh beef was a luxury only indulged in occasionally; but turtles were kept in the moat and killed whenever we wanted them.

As I was not accustomed to the methods of preparation in vogue on the reef, and not wishing to unnecessarily expose my ignorance, I concluded "that discretion was the better part of valor," and pretended to be very busy in the house, so that on those days Eliza was mistress of the kitchen.

The first time she prepared green turtle a very fine soup was served, followed by what she called turtle balls.

After dinner Eliza asked me how I liked it.

I replied very much, only the next time we would try it without onions.

They had brought me a quantity and I had told her to partly cook what was left, to be sure that it would keep.

The following afternoon she came upstairs and said, "What shall we hab for dinner, Missis?"

"Why, the turtle balls that were left yesterday," I replied, "and whatever vegetables we can get, with a pineapple tart."

She looked at me with a queer expression, finally bursting into an embarrassed laugh, and said, "De Lor', de Lor', how funny. Yo' 'spect to hab dem balls for dinner, and I and Jack and Lewis dun eat 'em all up las' night. De Lor', de Lor', I eat five, like to kill me, and Jack say he neber eat sech balls on dis yer key fore."

"But," I said, "you told me you did not like them, never ate them, and I gave you bacon for your dinner."

I suppose she saw a look of dismay on my face, for she stopped laughing and said:

"I'se sorry, Missis; I tout you didn't like 'em wid de onions, so we dun eat um. De Lor', want dey good."

"Well," I said, as a dinner without meat seemed to be the prospect, "make an ochre soup and we will do without fresh meat to-day," and she left me, as I thought, with rather a woebegone expression.

When the soup was served at dinner, the ochre was certainly not in sufficient quantity to warrant its name, and I said, "Why didn't you put in more ochre?"

"Why," she replied, with a toss of her head that endangered the foundation of the yellow turban, "want time, Missis, want time, guess ise made soup afore."

"But ," I said, "it would not take any longer to cook all you had than a few."

Seeing there was no help for it, the confession very awkwardly followed, that they had eaten the ochres too.

I then learned that I must treat her like a child, giving her what she was to have, and telling her what to serve us.

I had learned that planning one's meals at the Dry Tortugas depended, in a great measure, upon one's wits and ingenuity.

The plan was to bring us fresh beef from the mainland once a month; but the best of intentions fail sometimes and our supply was no exception to that rule.

Time sped very rapidly notwithstanding our necessarily monotonous life, the greatest events of interest consisting of our mails; and the delight with which we hailed the sight of the mail schooner Tortugas over the top of the fort when we looked out in the morning never abated.

No orders of removal had yet arrived for Captain Woodbury, although they had spent four years there, so they decided to go North for the summer.

Our intercourse had been so delightful that the prospect of living there without them was appalling; for my husband had become so interested in his scientific labors he had planned to remain another year. Our household goods had arrived from the North some time before, so that the home began to look cheerful; yet Mrs. Woodbury's piano and large family nearly always attracted us there in the evenings.

The mornings were devoted to lessons for the young folks, but the afternoons invariably found us on the water or wandering over some of the adjacent keys, where the boys became apt pupils in the study of natural objects.

Our evenings after the little folks were asleep we spent together, reading aloud or with music and conversation; and the peaceful, happy life we led I think was often, by all of us, looked back in the sorrowful years that followed, if not with longing, with great pleasure.

They were sad days before and after Captain Woodbury's family left, for it took some time to adjust ourselves to the loneliness that followed; and I never shall forget the peculiar sensation with which I watched the schooner Tortugas float away with them all one bright moonlight night, leaving us almost alone upon this sand bank on the borders of the great Gulf Stream. The Fourth of July of 1860 passed very quietly. Our greatest annoyances now were the delay of the mails and the scarcity of good things to eat. We wearied of canned food, and pined for fresh vegetables that were not. Even green grass to look at was a premium. Green turtles and fish we had in abundance, and, occasionally, a pig was killed; but we longed for more variety. The fowls were poor from not having the proper food, and coral sand did not answer as a substitute for gravel. We sent to Key West, sixty miles away, for any and all kinds of vegetables that Captain Wilson could find; but he returned with the word that there was nothing in Key West but a few onions, which were quoted at one dollar per small bunch.

We had excellent rainwater to drink, caught during the rainy season in large reservoirs. Ice was an unknown quantity on the Key and twenty cents a pound in Key West. If we had ordered it, and there had not been a stiff breeze, it would simply have resulted in our providing the boat's crew with ice water, and having the pleasure of paying for it; so we kept our drinking-water in porous jars called monkeys, which hung in the shade, keeping it sufficiently cool. The butter would have been benefited by ice if we could have kept it all the time, but to be frozen one day and dealt out with a spoon the next day would, in all probability, have had a bad effect upon it; so we kept it in as cool a place as we could find, and it was test of the temperature whether a knife or a spoon was placed by the side of the butter dish. It was usually a feast or a famine, and just at that date the latter state seemed to prevail.

The flour grew poor; the weevils shared it with us; we could see them flying in the air near the casemate where a quantity of flour was stored. We grew hungry for even some of the lean things of the land; but we did not lose our spirits or cheerfulness. The first of August a steamer arrived with our own private stores of canned fruits and vegetables from New York, and, better yet, with news of an appropriation for the forts, which meant more comforts in the way of livestock and new life generally.

The mail boat brought us bananas, fresh beans and, best of all, a box of good things from home; and to say that we were excited and happy rather proved that we were previously in much the same state Aunt Eliza complained of when I tried to hurry her,-"stagnated."

During August and September we had a succession of fearful thunderstorms that frightened me more than I cared to admit. They continued for nine days in succession. Even the old fishermen acknowledged them to be unusually severe. The thunder echoed and reverberated through the arches so that it seemed as though the whole fort was going to tumble down about our heads.

The heat was intense, and the mosquitoes distracting. As the Tortugas brought no mail, a month without letters was almost as trying as going without food. August found us in low spirits.

Finally the transport arrived; bringing us fresh beef, the first we had seen in four months; and, having some onions and potatoes, we feasted. The great delay was thus explained by Captain Wilson: he had purchased some fresh meat for the fort, and was all ready to sail when a squall came up without warning; and he was obliged to take it back to the butcher's ice-box and wait for the gale to subside. When it had spent itself he made another purchase; but the elements were in a capricious mood, and, fearing a calm would be as disastrous to his cargo as a gale, he again appealed to the butcher, who this time refused to take it back, and it was packed in ice, we reaping the benefit.

Aunt Eliza often spoke of "broiling her brains it was so hot." I now felt that it might almost be possible.

The rainstorms continued up to October, but more gently; yet to the north of us a number of wrecks were reported.

It did not take much to rouse the residents of the island to a state of excitement; and when the Tortugas came back one morning, after having started for Key West, with a deserted wreck in tow, a crowd soon assembled.

It was a sad sight. Both masts were gone, and there was a great hole in the side which had been stopped with the bedding. The rudder was gone, but they had made a temporary one which suggested that the crew had survived the worst of the gale and been taken off, which was the case, as we heard that a vessel from New Orleans, bound for Liverpool, picked them up and landed them in Havana.

There were fifteen on board the hapless craft, some women and children. The vessel was from Trinidad, bound for Cuba, loaded with fruits in glass jars, and wines, which were afterwards sold in Key West. Several dismantled vessels went into Key West that could not make our harbor. One that was spoken was out of water and provisions. They hoped to make Key West, but, as they did not, it was feared the vessel went down. The gales at that season were to be dreaded as there was so little warning; and yet they did not call them hurricanes, which they were to all intents and purposes. Even Aunt Eliza began to tire of the Dry Tortugas.

She was evidently in a "low-down state," as she announced one day that she was, "De only one lef' of all her fambly."

Thinking she had heard some bad news, I asked, "Where are your brothers?"

"Oh," she replied, "dey is in Sabanna, but dey might as well be dead; I neber see um 'gin," and she would "not las' long herself. De rheumatiz got above my knees now." Then she would take her pipe and smoke until she was dizzy.

About the middle of October we had our first norther. The mercury fell from eighty-five to seventy-five degrees; and we all took heart as we inhaled the cool air.

Just before the norther a vessel drifted upon the reef off Loggerhead. Had the norther held off a few hours even, she might have been floated, as the wrecking-smacks were trying to lighten her; but there was no hope after that. She was driven up where the sharp coral crushed a hole in her; and the water was soon even outside and in.

There was rumor that the vessel was allowed to float upon the reef, which would account for the wreckers being so promptly on hand. Such things had been done; but no one felt positive enough to make such an assertion openly.

I was glad to have the hurricane season pass without a genuine one. As an example of the suddenness of the squalls, one day while we were at the dinner-table it grew suddenly dark; we rose, walked through the hall to look at the clouds, and before we could return to the foot of the stairs, half way from the front door, the squall struck the island with such violence that a chair, standing before a long window on the second floor, was blown across the room and a hall and half way down the stairs, and the rooms flooded with water, while it grew so dark that we had to light the lamps. No wonder we were glad to have the season for such performances over.

The irregularity of the mail was exasperating, as it was our only connection with the outer world; and to wait three weeks again for a letter or any news from the North made us almost desperate.

The last detention was caused by a disabled steamer at the mouth of the Mississippi River; for our mails came in various ways, there being no regular mail contact for Key West. The railroad was under water up the coast, so the mail was sent to Mobile to reach the New Orleans steamer. The schooner Tortugas waited a week for the mail, then started to come down without it, but sighting the steamer returned, even then being becalmed twenty-four hours in sight of Key West.

A rumor now reached us that Captain Woodbury was coming with Captain Meigs* by the next boat, which meant a change in the command.

We watched most anxiously for the boat, spending the afternoon on the ramparts with the glass; but the horizon showed nothing that came out of the regular course to New Orleans until nearly night, when we discovered the black topmasts of what we thought was the Tortugas; but it was so calm there was no hope of her reaching us for hours.

We could see the wreck away on the other side of the fort with its fleet of schooners looking like a harbor in the midst of the sea; but the darkness came on with the Tortugas scarcely any nearer. At ten o'clock there was no word, and by midnight we gave it up and went to bed, to be awakened by the watchman calling to the clerk of the office that mail was in. Of course sleep was out of the question until I knew of the arrivals, and how I should manage if the guests had arrived.

Captain Wilson had been ordered to have the flag at the peak if strangers were on board, but in the darkness we could not see. After a while one pair of feet only came into our hall; and we soon heard that there was no mail, that Captains Woodbury and Meigs would come on the next boat, also that the mail contract had been given to the Isabel, and that hereafter we could look forward to a regularity in the arrivals,-a great relief.

Disturbing political rumors that for the past six weeks had been in the air without giving us any special uneasiness seemed to increase; yet we gave them little thought, considering them as evidences of a strong party feeling, perhaps increased by the nomination and election of Lincoln.

Being surrounded by people of Southern sympathies, we heard little except their side of the question, and the one of appropriation for the forts. The latter was an all-important one to them, as, if it failed, there would be hundreds of slaves without employment,-a serious matter to slave-owners who had to feed and clothe them.

The next boat brought Captain Woodbury, Captain Meigs, his clerk, Dr. Gowland, and Mr. Howells as draughtsman.

Captain Meigs accompanied him to Key West, returning by the next boat, which also brought a friend and her maid, to make me a long-promised visit, and my husband's brother,-the letter a most delightful surprise. My new cook proved a treasure; and all this made quite a revolution, and for a few weeks I felt that civilization had overtaken us. My guest brought her beds for herself and her maid, needing them on the boat; so that they were provided for.

We enjoyed the bustle and commotion of people about us, and the return to some of the conventionalities of life, which so much time spent upon the water had interfered with. To add to the life infused by all this, a man-of-war, the Mohawk, Captain Craven,* came into the harbor. The following day I gave a dinner party of twelve covers to Captain Craven and his officers. With a market sixty miles away, one's wits did extra duty. But the dinner was apparently a success, if one could judge by the appearance of the guests; and to us, who had been so long deprived of society, it was a delightful occasion. The next day the gentlemen took the Tortugas and went fishing, and the following week was a gay one for all.

Threatening news came by the next boat. Sometimes when we heard Captains Meigs and Craven, who were so recently from the active world, discussing the state of feeling in the South, it made us a little apprehensive, but that soon passed away. The idea of a civil war seemed impossible.

A few weeks later it became so desolate at Tortugas that I accepted an invitation to visit Key West.

The climate here was perfection at that season of the year, with much less wind than we had at Tortugas; and it was a delight to go about the streets, into real stores, and to visit people after our seclusion for so many months.

During my visit Captain Craven arrived with two slave ships, captured off Havana, that had just started for Africa.

The following day came the election for candidates to attend the Secession Convention held in Tallahassee. The secessionists were victorious, and announced boldly that they would take Fort Taylor at Key West.

Rumor also said there was no money in the State treasury; that the Governor had taken it to send North for ammunition.

A rather decided secessionist told Captain Brannon, who was in command of the fort, that they would starve them out. His reply was that he could drop a ball into his house that would bring out all the provisions they wanted.

I wondered at the good feeling where so much spirit was displayed, and tried not to be drawn into any discussion, as I could not believe there would be anything more than a war of words.

The day before Christmas Mr. Philor placed his carriage at our service, and we drove to some gardens where all the trees and shrubs were new to us, a perfect tangle of tropical growth, even to a Banyan tree. Then we drove to the fort, which was the end of the drive in that direction, and to the barracoons where the slaves were kept until they could be sent to Africa. Those here were taken by the U. S. S. Powhatan some months before. It was a sorrowful sight, and brought home the horrors of slavery more intensely than anything I had ever seen before.

Christmas was more like a Northern fourth of July in temperature and noise. We attended service in the morning, met numbers of our friends, and spent a most delightful day; and at night some of the officers of the Mohawk gave us a serenade that made a delightful ending to the holiday.

Captain Meigs stopped on his return from a trip to Havana, bringing the news of the secession of South Carolina, Captain Hunt joining him to talk over the outlook. It began to look cloudy at least; yet no one thought there would be a civil war.

The next Sunday a proclamation from the President was read in church "of a day for fasting and prayer" on account of national trouble and the prospect of a civil war.

The few remaining days of our visit were spent in returning the calls of the many pleasant people who had entertained us. There were so many delightful and homes it was sad to think what might result from the feeling that would show itself in spite of all courtesy.

Captain Meigs and my husband talked of a trip to Tampa, after which we were to return to Tortugas, as we had already remained away longer than we intended.

On January 1, 1861, a rumor came that Mordaci, the owner of the Isabel, had offered her to Carolina for a man-of-war, our mail contract going with her.

There was a cloud on the horizon that looked larger than a man's hand, and it affected our spirits. People began to be suspicious of their neighbors. Those who claimed to be Northern sympathizers owned their servants. There were many Southerners in Key West; but a goodly number were originally from the North, who, dwelling many years in that climate, and owning simply their house servants, were doubtful whether, if Florida seceded, they ought not stand by the State of their adoption. The Northern residents who did not own slaves were true Unionists from the first. The slave seemed to be the turning point. The Conchs, as people from Bahama were called, were boisterous in their demonstrations of loyalty to the South; but, at the first suggestion of their doing duty in case of necessity, they packed their goods and sailed for the British Isles.

One morning the first news that greeted the gentlemen on the street was that the militia of the town had attempted to take Fort Taylor during the night. A futile effort, however, as Captain Brannon had sent the two companies of regulars from the barracks the night before after dark, leaving the harmless gun carriages covered, so that no one suspected the removal of the guns. Captain Hunt had turned the workmen into soldiers, and they had been employed all the previous day in taking the wharf away and every available means of entrance; so that an unexpected bath would have been the result of the attempt to gain entrance over the planks innocently leading to the open spaces.

A great state of excitement now prevailed. Letters that were sent to Washington were opened and destroyed; and our own from the North were delayed purposely, and sometimes not forwarded from Charleston, so that we began sending our mails north via Havana.

I was beginning to weary of the very name of secession; for there was little else discussed, and it made us gloomy if we allowed ourselves to dwell upon the outlook, although no one yet admitted that there was to be a war.

Affairs began to assume such a serious aspect that Captains Meigs, Hunt and Brannon held a council on board the Mohawk, resulting in our leaving for Tortugas the next day. Captain Maffitt met with the officers, but he resigned the next morning, leaving his ship there; he afterwards commanded the Confederate privateer Florida.

There were joking remarks made by our friends that if we found the fort in possession of the secessionists we could return,-not in the least cheering to us, although we treated them with as much levity as they did; but I think when we were near enough to our little island home to discern with a glass that the flag that floated over it was the stars and strips it was a greater relief than, perhaps, any of us wanted to acknowledge.

Our defenseless situation was almost an invitation to the enemy to capture us; and why they did not was rather a mystery to us. The WyandottZ˙, we heard, was on the way to take possession of both forts, and could have taken Fort Jefferson simply by steaming in and claiming it; for there was not a single gun on the island.

Active work began on our return. A drawbridge was made and raised every night, all communication with the outside being cut off.

The evening of the seventeenth of January Captain Meigs called, and I remember his reading Shakespeare aloud, and discussing some of the historical plays with my husband. They were both students of Shakespeare. In the midst of it Mr. Howells came in saying that the sheriff had arrived from Key West to arrest the fishermen, and they had sent for Captain Meigs to intercede for them.

The facts of the case were that the State of Florida had made a new law that none of the fishermen could obtain a clearance to go to Havana without paying a fine or license of two of three hundred dollars. Of course they could not pay it; and the object was to drive them home. They were mostly from Connecticut; and there were fourteen smacks in the harbor. They came down every winter to fish, taking their catch to Havana market.

Captain Meigs sent word to them not to pay it, and to the sheriff that he was Governor of that island, and he had better return to Key West. Then he sent Mr. Howells off privately that night to Key West for guns. He felt it was time to take the responsibility, even if he was censured for it.

I asked if he apprehended any danger. He looked at me as though he were thinking whether it was best to alarm me, and said: "No, Madam, but I want to be prepared in case of emergency. If we had a few guns we should not be molested. Guns are not so much to use as to keep people away."

He was the man for an emergency; and I think General Scott, instead of censuring him, praised his prompt action fully.

The following morning, January 18, 1861, our excitement culminated in the news that a man-of-war was in sight and steaming up the harbor. Every one was wild with excitement, running to the bastion with glasses to see what flag she floated; yet even that might have been a deception if it proved to be the red, white and blue. But she carried no flag, a fact we considered suspicious.

Captain Meigs sent Dr. Gowland to meet them as they stopped outside the reef, sending a boat ashore in a spot known to us as very dangerous, unless the navigators knew the channel exactly. It was a narrow opening in the reef, called the "five-foot channel," and only used by our small sail-boats. Dr. Gowland carried orders, that if they were enemies they could not land. A verbal resistance was the only one he could offer, but as soon as the two boats met a signal was given to those on board the steamer, and the stars and striped flew to the masthead. The feeling of those who were watching from the fort can better imagined than described; and none of us realized the tension we had been under until this relief came.

It proved to be the steamer Joseph Whitney, with Major Arnold in command, from Fort Independence, at Boston, with troops for our relief.

The reception they received must have left no doubts in their minds regarding their welcome. We were more than overjoyed; and the commotion and excitement of unloading the steamer, for she was to return immediately, as her expense to the Government was six hundred dollars a day, was something that tested the ability of every one. It did not take long to put us in a state of defense and everything in military order. We were now aroused at sunrise by the reveille. A sentinel walked in front of the guardhouse, at the drawbridge, and one was posted in the lighthouse tower.

Already our quiet life was a thing of the past. The large guns came from Key West, were soon mounted, and we began to feel as though we were on a war footing. Yet with all this Major Arnold did not think there would be war, and we surely hoped not. The New Orleans boat was taken off, and our only method of sending and receiving mail was through Havana, where the schooner Tortugas was sent for it.

The papers now received were old, but did duty all over the garrison. The officers would meet and discuss the prospects; but even the firing on the Star of the West in Charleston harbor did not convince Major Arnold that we would have war.

I presume we heard strange rumors that never made an impression at the North, they were so quickly followed by others of greater importance. The news from Pensacola was warlike. Two thousand men surrounded the fort; and the commanding officer's wife going into town to do some shopping was taken as a spy and detained as a prisoner. It was said that the Senator from Florida, before he resigned, examined the plans of Fort Jefferson and Fort Taylor in Key West. Captain Meigs thought if he came there then he would find something not in his copy.

When Florida seceded she reappointed all the old Government officers; and my husband was told that under the new law he was a member of the Engineer Corps.

Those were very exciting times to us, not that we expected to be attacked, but we were within the line of attraction. We heard that the officers in Washington had concluded to send their families out of the city. Captain Meigs advised his family to go to Philadelphia. How strange it seemed to think of such things in our own country.

At this time two large ships-of-war came in bringing guns and news of more troops on the way. One of the ships came from Portsmouth, N. H., where it was thirteen degrees below zero. Major Arnold said that he expected to find us in the hands of the secessionists. General Scott gave him orders that if the fort had been taken to retake it if possible; if he failed, to cruise around Fort Jefferson for sixty days, with the understanding that he was to be reinforced by a war steamer from Pensacola. January 22d the Mohawk came back to ply between Key West, Havana and Tortugas regularly. All the able-bodied men had been put upon the roll, and guns and ammunition dealt out to them. At that time there were in the harbor two steamers of war, one side-wheel steamer, a revenue cutter, two barges and some dozen sloops and schooners. We were no longer out of the world; yet the steamer Magnolia from New York stopped and left a month's collection of mail.

The last of February brought news of the secession of six of the Southern States, and that a Southern confederacy had been formed at Montgomery, Ala, with Jefferson Davis as President. On March fifth Lieut. Gillman arrived with Major Tower of the Engineers, having arrived in Havana from New York just in time to come over in the Tortugas. Lieut. Gillman belonged to Lieut. Slemmer's command at Fort Pickens. He was granted permission to go through the invested district, but preferred going that way and landing under the protection of the stars and stripes.

The two coast survey schooners were there at the same time with Lieut. Tirrell and three assistants on their way to New York. They were at Charleston Harbor, but their tents and instruments had been stolen, and they concluded to go to Havana, sending their schooners home; but we kept one of them, as the Tortugas had to take Lieut. Gillman to Pickens with dispatches from General Scott to Lieut. Slemmer.

Soon after this we had a great disappointment in the order that came for Captain Meigs to return to Washington. We could not help rejoicing on his account, yet felt that half the life of the place would go with him.

Captain Hunt came down from Key West to take charge until relieved; but fortunately for him the New Orleans boat came near enough that night to quietly send a boat ashore with Lieut. Reese, who had unceremoniously been put out at Fort Gaines at Mobile, without even having time to remove his personal property. He came to assist Lieut. Morton, whom we expected to fill the place vacated by Captain Meigs.

Lieut. Reese said that he was looked upon with great suspicion on board the steamer, as he was taken out to it in a small boat ostensibly as a passenger for Havana; but he told his story to the captain, who made an excuse to stop for fuel, and so landed him, as much to his own surprise as ours.

He of course had news from the Southern posts to give in exchange for much that we could give him, for he had been entirely alone. All the workmen left him; but he could not leave the fort until had had orders to do so from Washington or it was taken from him, the latter not a difficult thing to do. He was very glad to get among friends, and was a pleasant acquisition to our now constantly changing society.

One day a little smack came into the harbor flying the Palmetto flag, the first we had seen. Major Arnold sent word for him to haul it down and put up the proper colors and salute them. He was promptly obeyed, and they came and apologized.

The steamer Daniel Webster now arrived with provisions and recruits, but took the latter with her, as she was going to Texas to meet the five companies that were leaving the dust of that State behind them, as it had seceded and General Twiggs had been dismissed from the army.

Work was going on rapidly. The engineer had a large force at work on the bastions, where they were to mount six heavy guns. Everything was bustle, and a great deal was accomplished in a very short time. Reports from Key West were very unpleasant. Officers of the army were followed about the streets and insulted. Some of the mob were annoying peaceful citizens, threatening to take our schooner and Fort Taylor. One copy only of Lincoln's inaugural address came to Key West. It was kept quite a week before it reached us at Tortugas; and people there thought they could smell gunpowder on it.

I think, for its size, Fort Jefferson was one of the busiest places on the continent at this time; and the excitement was kept at a fever heat, either by some stray rumor from the many vessels coming in, or the detention of the mail and a dearth of reliable news, making us apprehensive of the imaginary evil.

The horizon was watched, not only by the sentinels, but by every one. I remember, one day, before the troops came, that Captain Meigs discovered smoke away to the southwest, as of several steamers moving in a very suspicious manner to us, who were so on the alert and were almost expecting invaders.

We all went to the ramparts and with glasses watched them, making out distinctly ten or twelve large vessels steaming about with concerted movements; and we could hear heavy firing. But they came no nearer; and, after watching a long time, we came to the conclusion that it was the Spanish fleet of war practicing, which we found to be the case some days afterwards, from a fishing-boat which had been near them.

The last of March, 1861, the steamer Daniel Webster returned, landing one company, reporting the Rush just behind with the others. The Webster came early in the morning; and just before dark the Rush arrived, with a band playing patriotic airs, the troops cheering lustily.

It was a motley crowd-camp women, children, and all the paraphernalia of camp life. A portion of them had marched from Forts Duncan and Brown some four hundred miles down the Rio Grande to Brazos; where they took the steamer.

On the way the rear of the battalion had an engagement with the Indians, during which several of the latter were killed. The Indians had commenced hostilities as soon as the troops were ordered to leave the State.

The officers had sent their families home by way of New Orleans, as they did not know how long they would remain or what kind of a place they were coming to.

There was discontent and disaffection among them; and two of the officers before many days sent in their resignations, as the State they came from had gone out of the Union.

We numbered at that time about four hundred, and represented a busy little town. The fort at night was brilliant with lights, and the place was active with the bustle of many people.

All this commotion brought comforts in the way of food to us who had only seen fresh beef and vegetables semi-occasionally; for a steamer was chartered to bring us six cattle at stated times, with other necessaries.

The Tortugas returned from Fort Pickens with no news except that Major Tower of the Engineers was not allowed to land, having to remain on the Brooklyn.

Lieut. Morton and his two assistants arrived, proving a most energetic and efficient officer, one whom we like exceedingly. He had just returned from making a survey for a route across the Isthmus of Panama. Naturally, none of the officers fancied being sent here; it was like imprisonment when there was so much excitement in the North, but they all did their duty conscientiously.

On April fourth a loud call from the sentinel on the lighthouse tower announced a steamer; and as usual we took the glasses to the ramparts, where could plainly be seen a vessel loaded with people; and on the wheel-house we distinguished officers. We felt that there were as many people on the island as could be accommodated, and wondered what it could mean. As the steamer neared the wharf, to our great surprise we recognized Captain Meigs. The other officers proved to be Col. Brown and staff, and they had come under sealed orders. When Captain Meigs called to see us, I asked him what it all meant.

He laughed, and replied: "That is a secret. No one but Col. Brown and myself know; but what we are here for is to get some light guns, Lieut. Reese, an overseer, twenty negroes, thirty men, a scow and a load bricks; and we can only stop two hours and a half."

They brought papers only a week old, but new to us. They had on board four hundred men besides the officers and crew, and sixty horses.

Lieut. Reese had that morning arrived from Havana with an assistant of Captain Hunt. He joined the excited party; and before dark they were steaming out of the harbor, with the schooner, scow and a load of bricks in tow.

The destination of Captain Meigs and his party was a secret. It naturally aroused much conjecture on our little island; but we soon heard that the expedition had arrived at Fort Pickens, and that the object was to reinforce the garrison there. Even this movement did not convince our genial commander, Major Arnold, that war was imminent; yet with the vigilance of the soldier he was prepared for the struggle that was to come, and began a series of fortifications that would have made the island a difficult place to capture. In fact, fully armed, the Dry Tortugas was almost impregnable; and everything pointed to the conclusion that the garrison would soon be in a position to defend itself against the world. The outside fortifications began with a breastwork on Bush Key, which hitherto had been the home of the sea-gull. The trees were cut and made into facines. Sand Key was to have a battery; and finally we learned that the fort was to become a naval station, vessels being on the way with stores.

Key West was now under Federal authorities. New officers were appointed, to command the four hundred men on the ground; and we were assured that more would be sent if necessary. I asked Major Arnold if it was fear of a foreign power that all this preparation was being made, as no one thought England or France would acknowledge a Southern confederacy.

He replied that possibly the Government thought that, in case of war, Spain might stand ready to pick up what spoils could be easily taken during a national explosion.

Lieutenant Morton now went to Key West for shovels, wheelbarrows and workmen. He had sent to New York for three hundred men, and some sappers and miners, who came on the last boat; and work on Bird Key began at once.

One day men discovered a large cannon several feet from the shore in very good condition. It had been spiked, and had the English arms and date of seventeen hundred on it. We invested it with a romance at once, probably not far from the truth, as it belonged to the pirates; who must have been followed, and who had spiked and thrown it overboard to prevent it from falling into the hands of the enemy.

These islands were known to have been the resort of Spanish buccaneers years before. Captain Benners, the lighthouse keeper, found several thousand dollars in Spanish doubloons on East Key, ten miles nearer Key West; and many stories were told of other finds.

It was summer; the men worked bravely in the broiling sun. The mercury stood at 91 degrees on many days; yet no case of sunstroke occurred, but other troubles came. The men began to have scurvy for want of proper food, and some had to be sent North.

The day we received the news of the attack on Fort Sumter was a memorable one. The officers were demoralized; for none of them, I think, had fully realized that the end was to be war, and the country scenes of bloodshed. They felt as restless as though they were imprisoned. All wanted to go to the front, and share in the glory and excitement; and it certainly was very trying to remain here doing nothing but guard a fort that now would not in any probability be in danger of an attack, so well fortified were we.

They told us that if there should be an attack the women and children were to be put in an empty reservoir under one of the bastions farthest from the enemy; and our plans were all laid, and rehearsed by the children day after day.

One day, after having been to Bird Key, we saw a very dense smoke on the horizon, which was moving slowly along. Speculation was rife at once. As we came up the walk Major Arnold called from the upper piazza to know if we were going out on the water again, as sentinels were posted on every side. The large guns were loaded and two brass field-pieces in the gateway were also prepared, with the men ready to use them at a moment's notice.

My house boy told me that there was a rumor that the fort was to be attacked, and that a workman, an American lately engaged, who came from Havana, had been arrested as a spy but that they were not able to prove anything against him: a sample of the rumors in our little settlement.

The next morning the steamer was still in sight, going back and forth in a mysterious manner; and we could see that some sailing vessels had joined her. They disappeared before night, however, and we heard nothing from them; but later news came that the Confederate yacht Wanderer was out as a privateer by permission of President Davis; so we concluded that it was she, while the steamer might have been a convoy.

One day I suddenly heard the sentinel on the east face shout, "Corporal of the guard, post number one," in a shrill, excited tone. This was taken up by the next sentinel, "Corporal of the guard, post number one," still another repeating it, until the word reached the guardhouse. In a few moments a corporal went up the walk on the run, and I soon saw him on the fort; then the men began to go up; and soon we were all on the ramparts. Away on the horizon was a steamer headed for the channel. The suspicious black smoke was rising every moment. She evidently knew the channel.

My husband was the health officer; and I soon saw his eight-oared barge pulling across the Long Key reef with the officer of the day. It was their duty to intercept the vessel off the second buoy. On came the steamer, a black, suspicious-looking craft, still showing no signal; and such headway did she make that she passes the Sand Key buoy before the barge reached her, and steamed on rapidly, paying no attention to their signals, heading now for the inside buoy. The long roll was sounded, the men fell in; and in a trice the big guns were manned, and with a roar the first gun belched forth its warning from the Dry Tortugas. A solid shot whistled across the bow of the incomer so near the cutwater that half an hour later I heard the Captain say: "Well, Major Arnold, I must compliment you on that shot. Three more turns of our wheels, and you would have blown my bow to splinter."

The steamer was a transport in need of coal; and its officers had simply misunderstood the signals. They brought no news, except that the Spanish government had refused to admit vessels flying the Confederate flag into the harbor of Havana, which was in a measure comforting to us.

The following day the man-of-war St. Louis came in, her officers adding much to the social life of the Key.

During their stay Lieutenant Morton invited us down to see the oath of allegiance taken by Captain Wilson and the crew of the schooner Tortugas. It was quite an impressive ceremony, after which they were provided with two brass guns and small arms; and we called her our gunboat.

The coming in of so many steamers relieved somewhat the monotony of our lives; yet we did feel very far away, and the officers were still impatient at the isolation.

The Tortugas now went out as a gunboat, flying the stars and stripes, saluting it with thirteen guns. Captain Wilson evidently enjoyed his command.

A steamer came in with news to the eleventh, ordering the St. Louis back to Fort Pickens, and taking all the sand bags we had made to stop the open spaces in our second tier of casemates, as we had no fear of needing them then.

Anxiety continued to increase. Mutterings of war were heard on every hand. Neither side seemed likely to yield; and, if an agreement could not be brought about, it must inevitably result in that most horrible of all wars, a civil one.

The Southern States were arraigning themselves, one after another, like line of battle ships bristling for an engagement; and every man who had lived in any of these States immediately felt that his duty called him to stand by it, regardless of the Constitution.

One officer sympathized so strongly with three States that he had a fever of secession as each one threw off the yoke of allegiance to the Union; but he managed to stand by the colors he was educated under until the last of the three fell out of line, when he sent in his resignation, and became a noncombatant.

These were sad days, though sadder ones were to follow; yet I think no one dreamed that if war came it would be a long one. A few months would settle the difficulty. I think that was the feeling of all the older officers.

The population increased so rapidly that in June, 1861, the census was taken, showing that 550 souls were living on this sandbank of thirteen acres, too large a number we deemed for safety, little thinking that before long Fort Jefferson would be the home of several thousand men.

By enforcing a strict quarantine my husband kept the spectre of yellow fever, that was in Havana sixty miles away, though the strict confinement told upon us in other ways.

In June the gulls always came in thousands to lay their eggs on Bird Key, the season being in the nature of a festival and feast for us, as we made up egg-collecting parties. The eggs were enjoyed by us, as they were luxuries here. The quantity of eggs may be imagined when it is known that we could hardly walk in some places without stepping upon them, and would often take away a flour barrel full of the speckled beauties.

This year the men had taken possession of and were engaged in throwing up a battery on the island; and we were interested to learn whether it would result in the birds seeking some other place. At first they were shy and distrustful; but when they found that the soldiers did not disturb them they took possession of the old places, and could be seen from the fort hanging over the Key like a black cloud, while near at hand their cries drowned the voice.

On the night of the 1st of July we saw the comet of '61 from the top of the fort. Its appearance was sublime, as it extended over nearly half of the heavens. The colored people were inclined to be superstitious; and many wondered if the world was not coming to an end.

On the night of the 4th of July Captain Morton, whose nervous energy never seemed to flag, took us to Bird Key in the barge, with Chinese lanterns at the top of each of the two masts. The black boys accompanied us with their banjos and guitars, and made very sweet music. There we built bonfires and displayed some fireworks, celebrating our Fourth on this little coral island in the Gulf.

The afternoon had its excitement in the arrival of the steamer State of Georgia with two companies of Wilson's zouaves. It was supposed they were sent here as a safe place to drill them, as we had all the troops that were needed.

On the seventeenth a bark from New York came in, and also the steamer Vanderbilt from Fort Pickens, bound directly for New York. We concluded to avail ourselves of the opportunity of going North on a visit, and sailed on the evening of the 20th of July, leaving the fort with the most beautiful sunset for a background, the gorgeous colors streaming up behind, the fort looking almost as though it were going to be consumed in the blaze of glory that covered all that part of the sky. It was so impressive that we watched it from the deck of the steamer until the fort stood grim and dark against the sky.

We were four days going to New York. The steamer carried but nine passengers, officers who had been promoted and were going to join their regiments, all eager to go to the front.

The captain of the steamer had some fear of the Florida, which was cruising in those waters, and watched the horizon for black smoke. He kept one engine banked, as the steamer was short of coal, until we were up the coast beyond North Carolina, when he put on all steam, and we almost flew through the water.

When we took on a pilot off Barnegat we heard of the first Bull Run disaster.

During our stay North we visited Captain Woodbury in Washington. What a contrast to our visit of less than two years before, when the grass was literally growing in some of the streets; and it seemed a sleepy, restful place, where people took life calmly and enjoyed it. Now the streets were deeply cut by heavy wagons transporting guns. Everybody was rushing about with an excited air. Most of the men one met on the street wore uniforms significant of their duties; and we heard little talk beside war and rumors of war.

While here we also met Captain Meigs and Captain Craven, the latter there awaiting orders.

One day during our visit my husband came home and reported that he seen the smoke of the battle of Munson's Hill from the top of the Treasury, --a fact which brought home the reality that the seat of war was not far from the National capital. My husband felt that his services were need at the fort, as he was acclimated. So our visit was cut short; and we were soon on our way back to Tortugas, on the old transport Philadelphia, which we afterwards learned had been condemned.

We left in a driving snowstorm, and lay off Fort Hamilton until morning, when we took on board Major Haskins with one company of troops for Key West and some officers for Fort Pickens. My sister and Mrs. C-----, who was returning from a summer spent North, were the only ladies besides myself on board.

The old Philadelphia, was not the most reliable ship, but she carried us safely, and did much more duty even after she had been finally condemned.

The morning before reaching Key West Major Haskins surprised us all with reveille, which sounded very cheerful in the still morning air. Very soon afterward we met the Rhode Island, which hailed us and sent a boat with her pilot, and took letters from us for New York. She had on board an officer whom we left at Tortugas; and they also gave us the news of the bombardment of Fort Pickens, which place the steamer had just left. It was quite an excitement; for, although she was not more than one hundred yards distant, the little boats in going back and forth were entirely hidden by the waves.

The next morning found us anchored safely in Key West harbor, where we spent the day and left my sister with Mrs. C----in her lovely home under the cocoanut trees.

The next night at ten we were outside the buoy at Tortugas, where the captain of the steamer threw up rockets and burned blue lights; but no pilot came out until morning, when we were soon anchored opposite to the sally-port, where Captain Morton met and escorted us up to our old home.

There had been a great many changes during the few months of our absence. Major Arnold had left; and most of the troops had been exchanged; but one great pleasure I found on my return was in the addition of three ladies to the garrison.

I presume it will be difficult to realize fully the isolation of that kind of fort life,--even a great contrast to a life on the plains miles away from any town or ranch. We were in an inclosure of thirteen acres sixty miles from Havana, with nothing outside of the towering brick walls to walk on but a narrow seawall inclosing it, sixty feet away-- wide enough for two people to walk, with water on each side.

On the plains, if one wearied of their surroundings or were tired of their neighbors, they could ride out of sight, returning when they chose; but here it behooved people to keep up amiable relations with their surroundings, as they could not get away from them. I have been told by people who have crossed the plains, with parties who were most desirable companions for the first few weeks, that the isolation and constant companionship of the same persons day after day changed them entirely, developing freaks of nature unknown to them before, which proves that a change of scene and people is good for human nature generally.

This life was certainly a test of our dispositions in that respect; for we were entirely dependent upon ourselves for all our pleasures, and, I might almost say, comfort, for a want of harmony very materially interferes with that.

Captain Morton's assistant had brought his wife with him; and they formed a mess in the quarters we occupied before going North. He gave us the choice of remaining with them or taking a small house across parade which the Engineer Department was building. We accepted the house, remaining with them until it was finished.

The newcomers were Mr. and Mrs. J----, Mrs. R----, who had been an army lady, and Mrs. H----, whose husband had been promoted from the ranks. With Mr. Phillips' family, consisting of a wife, son and two daughters, and with the wife and niece of the lighthouse keeper, we could gather quite a party of ladies, making us feel much less out of the world; and we soon became quite sociable.

The increase of people brought many necessaries which added to our comfort, although everything was expensive: Butter fifty cents a pound, lard twenty, and other things in proportion.

The government began to tax all salaries exceeding eight hundred dollars, and many other things, which, with some whose patriotism was exceedingly sensitive when it touched their pockets so directly, caused no little grumbling. Later in the season, while my husband was on the mainland, he came across a camp of irregular Florida cavalry; and the following lines in pencil were handed him, nameless as to authorship; but whoever it was evidently felt that the cause hardly warranted all he was going through:

We are taxed for our clothes,

Our meat and our bread,

On our baskets and dishes,

Our tables and bed.

On our tea, on our coffee,

Our fuel and lights; And we are taxed so severely We can't sleep o' nights.

And it's all for the nigger!

Great God! can this be,

In the land of the brave

And the home of the free? We are stamped on our mortgages,

Checks, notes and bills,

On our deeds, on our contracts,

And on our last wills!

And the star spangled banner

In mourning doth wave

O'er the wealth of the nation

Turned into the grave.

And its all for the nigger, etc.

We are taxed on our office,

Our stores and our shops,

On our stoves and our barrels,

Our brooms and our mops,

On our horses and cattle;

And if we should die

We are taxed for our coffins

In which we must lie.

And its all for the nigger, etc.

We are taxed for all goods

By kind Providence given;

We are taxed for the Bible,

Which points us to Heaven:

And when we ascend

To the Heavenly goal

They would, if they could

Stick a stamp on our soul!!

And its all for the nigger!

Great God! can this be,

In the land of the brave And the home of the free!

Water was not a great consideration, with so large a garrison; and at this time the men were put on an allowance, it became so low. Fortunately we had the unusual occurrence of some hard rains and thunder-storms; and for a time the supply was sufficient.

All events were of consequence and even of importance to us, and without realizing that it helped to break the monotony of what would have been otherwise a very monotonous existence!

The building of the works had been suspended on the other Keys, as the feeling of security increased with our reinforcement of guns and troops.

We had a little excitement in the form of a suspicious-looking schooner that came in ostensibly in distress. Both topmasts were gone, and she was nearly out of provisions and water. Her captain said they ran the blockade; but they had secession passports, although they claimed to be fleeing from the rebels. Colonel Brooks ordered Captain Morton with four soldiers to go on board, after the captain had been put in confinement. They found two ladies and other passengers amounting to twenty people. Captain Morton said the ladies gave him their keys so pleasantly it made him quite ashamed of his duty. One trunk was very nicely packed with a hoop-skirt and a revolver in the bottom. They found the log-book notes very suspicious, besides their passports; but Colonel Brooks allowed them to go to Key West, sending a schooner after them to see if they went there or to Dixie again.

The command at that time consisted of one company of regulars under Captain Langdon, and four companies of volunteers,--Wilson's zouaves. Some of the latter were without doubt very questionable characters; and, as the officers had been chosen from among themselves, the matter of discipline had been so far rather a surprise to us.

There had been an order issued at headquarters that any soldier found intoxicated would be tied up. There had been no trouble, as in such isolated places that could be more easily managed;; yet the fishermen sometimes brought whiskey and smuggled it ashore, selling it to the men. But a vessel came in with stores; and some whiskey was carried to the commissary for safe-keeping while the soldiers were unloading the cargo.

We were going out rowing about half-past seven, when we heard a gun fired by one of the sentinels. Some men were seen running away with whiskey, the result being that on our return an hour later, as we came through the sally-port, a man was being tied up. As the officers passed him he called, "Tie me tighter."

We had been in our quarters but a few moments when there was a great uproar, a call for the guard, screaming, shouting and running from all parts of the fort toward the guardhouse.

Captain Morton, who had walked up to the quarters with us, hurried down, fearing there might be trouble with the engineers.

By the time we heard the call for Company M, the regulars; and the noise, which was still increasing, was most terrifying. We could hear the men loading their muskets, as they were in the casemates near the house, and saw them go down "double quick". Then followed more derisive yells, and for a few seconds it was quiet. We in the quarters knew nothing of the cause of the disturbance, as no one had returned. They left us with orders to stay indoors; that there would probably be no trouble. The order we could obey; but the statement we felt, with pale faces I dare say, was to be proven.