Recently, a colleague mentioned how well he thought the Technology Integration Matrix supported cybersecurity education. Huh? That caught me a bit off guard. The TIM is all about supporting ownership of learning and higher-order thinking skills, but doesn’t mention the word security anywhere. I’ve been involved with the development of the TIM since the beginning and we’ve never specifically thought about cybersecurity while formulating the indicators.

After some reflection however, I understood exactly what my colleague was getting at.

About a million years ago in Internet time, we thought we were doing well to teach kids a few basic security rules like Always use passwords with a mix of at least eight characters or Don’t click on attachments from strangers. And maybe a long, long time ago, a classroom poster of a dozen do’s and don’ts when using the Internet covered most of the bases.

That was then.

Nowadays, cybersecurity is definitely a moving target. In the past year, COVID-19 scams spread as fast or faster than the actual virus. The vast majority of security breeches now come from social engineering attacks. That super long password is useless if the fake “school IT guy” tricks you into giving it to him. That friend’s email with the attachment might not be from that friend at all.

A list of “rules” is no longer sufficient to keep students cybersafe—if it ever was. Sure, we should still share those basic rules of cybersafety, but even more important is to prepare students for the next wave of security issues that didn’t make it to the list of rules yet and to prepare them for life after they have graduated. Moving students to the higher levels of the TIM is one of the best ways to prepare them for whatever comes next.

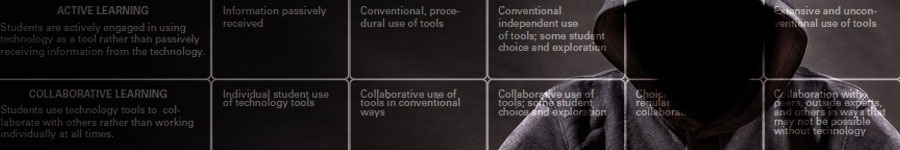

I’ve created the following table to contrast goals of the Technology Integration Matrix with the preferences hackers have for their intended victims.

What the TIM Encourages

What Hackers Want

Ownership of Technology. Students are independent and responsible in their use of technology.

Hackers prefer targets who don’t really feel that they own their tech. They’re used to just following directions and not taking responsibility for tech use on themselves. Such victims are easier to fool into following directions from someone impersonating an authority figure like tech support or a bank officer.

Metacognition. Students take time to reflect on their activities.

Hackers depend on victims not taking time to consider their actions. That’s why there’s usually an urgency to a phishing email or message. The hacks to the Twitter accounts of Bill Gates, Joe Biden, and Elon Musk this summer promised to double the target’s money, but only if it was sent within 30 minutes.

Collaboration. Students are experienced in using tech to interact with a range of others. They have become familiar with how people naturally interact with each other over technology.

Hackers are pretty good at impersonating others in email or other communications. An easy target is someone who just responds to the name of the person who allegedly sent the email, but really isn’t sensitive to the nuances that smell phishy.

Comfort. Students are confident and comfortable when using technology and making technology choices.

Scareware depends on the victim’s anxiety or general lack of confidence when using technology. Targets who lack confidence and comfort are likely to respond to a message that pops up in their browser alerting them that they have a virus and they need to install the linked software to remove it.

Big Picture. Students have gained a conceptual understanding of the tools they use. They get the big picture of technology and technology tools. They have used multiple tools in tandem so they understand interconnections.

Hackers love folks that don’t get the big picture—folks that don’t understand interconnections and are all too happy to access a password protected service when using a public Wi-Fi connection or to enter the name of their first pet on a website.

Keep that poster of Internet rules on the wall. Utilize whatever cybersafety curriculum your school or district offers. But also remember that the TIM is a great roadmap for producing students who have a deep understanding of technology, can think critically about its use, and are much less likely to fall for cybersecurity scams now and in the future.

Roy Winkelman is a 40+ year veteran teacher of students from every level kindergarten through graduate school. As the former Director of FCIT, he began the Center's focus on providing students with rich content collections from which to build their understanding. When not glued to his keyboard, Dr. Winkelman can usually be found puttering around his tomato garden in Pittsburgh.