We’re frequently asked why the Technology Integration Matrix (TIM) has five levels. It’s usually in the context of a district comparing the TIM to some other technology integration model. Often, the assumption is that they would be able to crosswalk the two models if only the number of levels were the same. Of course, assuming a relationship between two models just because they have the same number of elements is a little like assuming a relationship between the five varieties of apples and the five varieties of oranges at your local fruit stand.

Many currents came together in the formation of the TIM including Florida DOE leadership’s desire for a common vocabulary for EdTech across the state, technology integration research at USF, and observations we made while building websites of lesson plans and classroom videos at FCIT. There’s a whole chapter related to the development of the TIM in the Handbook of Research on Technology Tools for Real-World Skill Development,¹ but in this article, I’d like to address the purely practical aspects of how we arrived at five levels and why, as we’re also asked from time to time, there is no level “zero.”

Why five technology integration levels?

Over twenty years ago I was invited to attend an all-day workshop with the instructional technology department of a large Florida district. The ISTE National Educational Technology Standards and Performance Indicators for Teachers had come out in 2000 and the district had been quick to adopt the NETS (as the ISTE standards were known at the time).

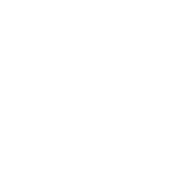

The district tech leaders and coaches all loved the NETS, but the topic for the workshop was how to make the NETS more meaningful for teachers. The consensus among the district tech leaders was that the NETS provided a pie-in-the-sky goal that they appreciated themselves, but that most of their teachers didn’t really find useful. They thought that teachers needed a practical, step-by-step path toward the NETS goals, not just the end goal. Putting yourself back as a teacher twenty year ago, you can probably see why that was true.

Below are the teaching, learning, and curriculum goals from the 2000 NETS for teachers:

III. TEACHING, LEARNING, AND THE CURRICULUM

Teachers implement curriculum plans that include methods and strategies for applying technology to maximize student learning. Teachers:

A. facilitate technology-enhanced experiences that address content standards and student technology standards.

B. use technology to support learner-centered strategies that address the diverse needs of students.

C. apply technology to develop students’ higher order skills and creativity.

D. manage student learning activities in a technology-enhanced environment.

ISTE National Educational Technology Standards (NETS) and Performance Indicators for Teachers, 2000

Adopting the NETS was the easy part. They looked great posted to the EdTech page on the district website, but what did it mean in practice to, for example, “manage student learning activities in a technology-enhanced environment”? Teachers already manage student learning activities. A teacher’s typical reaction to reading such a goal was probably along the lines of, “Oh super. They’re telling us to use more computers. Again.” Despite the fact that the NETS weren’t simply about using more technology.

The district tech coordinator at the workshop I attended was direct. She wanted some sort of ladder for teachers to reach the goals of the NETS. It wasn’t enough simply for the district to adopt the goals. She wanted her teachers to have what we now describe as an “implementation framework” to help them reach the goals.

The general goals of the NETS looked great, but lacked actionable steps to get teachers from point A to point B.

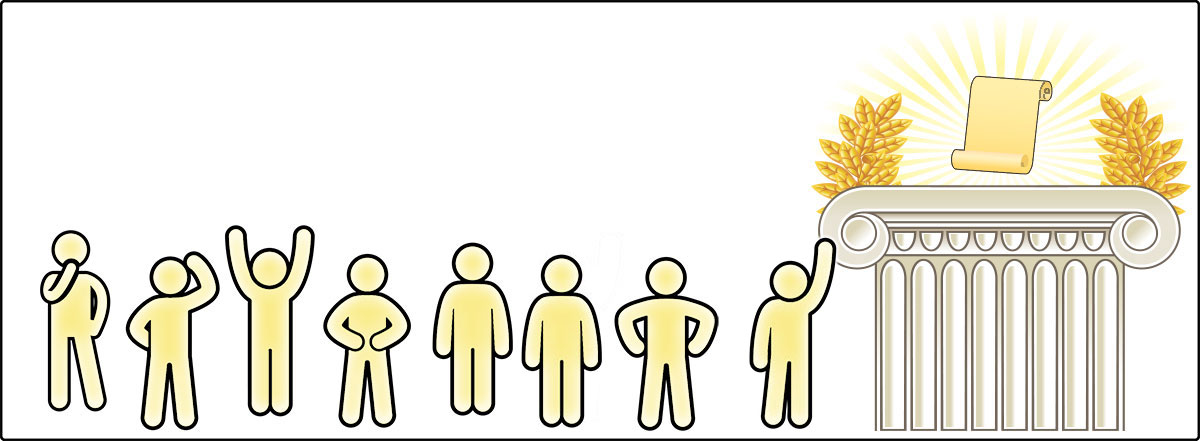

Real professional growth is a process. There are many steps along the way. To try to understand those steps, we reviewed academic literature, we observed classrooms, we assembled focus groups, we conducted structured interviews. And we collected many possible indicators of progress in technology integration.

Some steps were too big: Now that your students have just received their own laptops, allow them to use any application they want to fulfill any assignment.

And some steps were too small: Now that your students know how to use three applications, teach them how to use a fourth application.

But probably the most difficult aspect was to identify a series of steps that followed in a logical order as teachers grew in their mastery of teaching with technology. A mere checklist like:

◻︎Allow students to take their laptops home.

◻︎Give open-ended assignments for technology use.

◻︎Teach students proper Internet research techniques.

Are all good suggestions, but have no intrinsic order.

We sorted indicators. We argued. We covered the FCIT floor with notecards. And we field-tested possible combinations of indicators.

We considered many possible steps toward the goal.

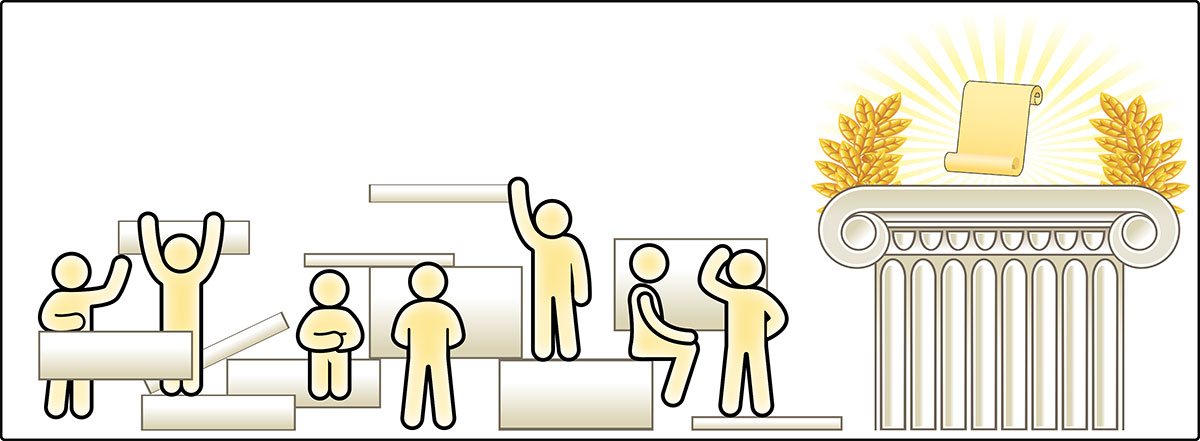

What became clear in our discussions was that the indicator for each step should meet the following criteria:

Specific. Each step should be described using specific indicators, not vague language.

Realistic. Each step should be realistic for the teacher. That’s not to suggest that every teacher will find every step to be easy or quickly achieved, but rather that each additional step is achievable with concerted effort on the part of the teacher and sufficient time to build student skills.

Observable. Each step should be described in terms of observable behavior of the student or teacher. Two different classroom observers should be able to agree on the level of a lesson because they are looking for observable behavior rather than nebulous descriptions of classroom atmosphere. This also increases the transparency since a teacher knows exactly what an observer is looking for.

Pedagogical Focus. We determined that each indicator should be related to teaching rather than to specific technology. This has allowed the TIM to remain relevant despite the vast changes in available educational technology over the past two decades.

Sequential. We wanted the indicators to follow a single, logical sequence that aligned with how a teacher would naturally grow in integrating technology in the classroom. Although the sequence seems almost self-evident in retrospect, this was actually the most challenging criterion to meet.

Success! Specific, realistic, sequential, and observable steps toward the goal.

And so, we ended up with FIVE levels that each provided a logical step. Each was achievable from the step before. They very closely matched the NETS end goals of technology-enhanced experiences, learner-centered classrooms, addressing the diverse needs of students, higher order thinking skills, and creativity. The levels formed a coherent progression that managed student learning activities in a technology-enhanced environment—exactly the end state that the NETS called for.

In subsequent editions, we added break-out indicators for the teacher, the student, and the instructional setting for each level and clarified some of the language, but the structure and distinguishing features of each level have remained the same.

Why no zero level?

People often ask why there is not some “zero” level on the TIM for those lessons that do not use any technology. I suspect the desire is to identify such lessons as especially “bad.” That attitude also seems to be more about rating a teacher rather than identifying the TIM profile for an observed lesson. It was no oversight that the Entry Level for a lesson includes:

- lessons in which no technology is used

- lessons in which only the teacher uses the technology

- lessons in which the technology uses the student (My shorthand for activities such as drill-and-practice exercises where the student does nothing but click a series of buttons responding to a series of questions. Shades of the Borg Warner System 80 teaching machines I encountered in my student teaching back in the 1970s. Your students will be assimilated!)

We wanted to have a level that was not seen as “bad,” but rather simply a home for all lessons in which the students were not actively using technology tools themselves. We specifically chose the name Entry Level to avoid negative connotations. It’s not a failure level. There are many perfectly valid reasons for a teacher to conduct a particular lesson at the Entry Level. Perhaps the teacher is introducing a new unit or topic. Perhaps the students do not have any previous experience with a technology and the teacher is following the time-honored “I do, we do, you do” model. Or perhaps the lesson simply does not support the use of digital technology. I’ve taught Art for most of my life. If I’m teaching computer graphics at the graduate level, I can get to the Transformation Level pretty quickly. If I’m teaching students to throw on the potter’s wheel, there’s no option other than for students to roll up their sleeves, don an apron, and stick their hands in the mud, although at other times in the same course the students may very well have opportunities to integrate digital technologies when it comes to the history, aesthetics, or criticism components of a ceramics course.

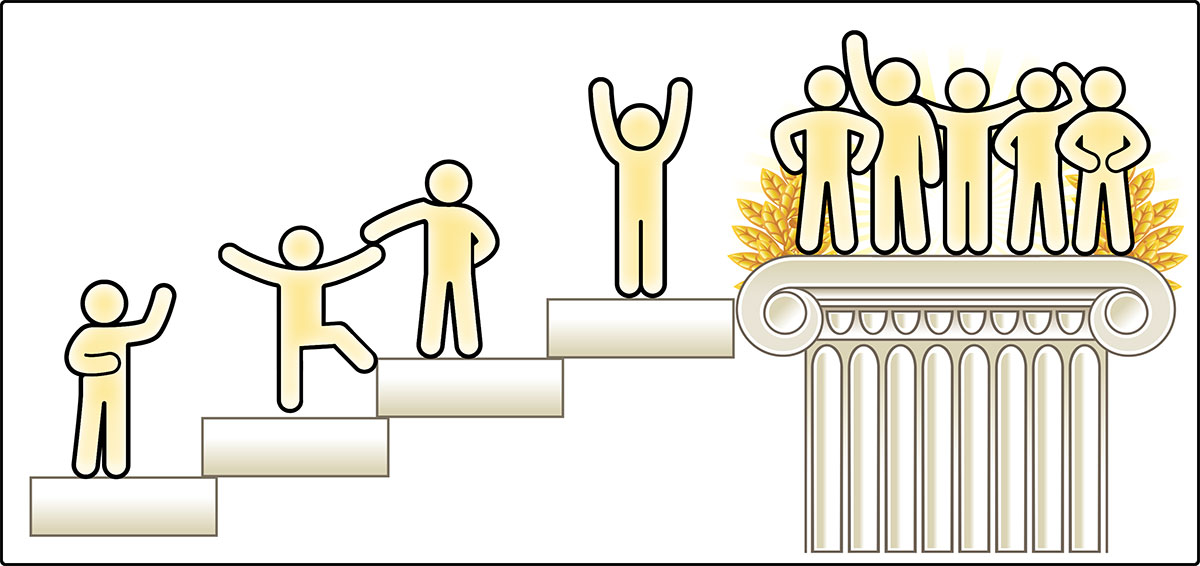

Remember, a TIM profile is always a description of a lesson, never of a teacher. Our goal for teachers is that they expand the range of TIM levels at which they can conduct lessons. A beginning teacher may only have a range of Entry to Adoption. After a year or two, depending on available technology and the students, the same teacher may have a range of Entry to Adaptation or Infusion. Hopefully, that teacher will eventually develop the ability to conduct lessons from the Entry Level all the way to the Transformation Level depending on the context, the curriculum, the available technology, and the needs of the students.

Postscript: One teacher’s journey through the five TIM levels

I came across Linda’s video a week ago and asked her permission to excerpt the middle section and repost it here. In this section, she describes how her natural growth as a teacher aligned with the five levels of the Technology Integration Matrix. [4 minutes. Transcript available.]

¹Ferrara, S., Mosharraf, M., & Rosen, Y. (2016). Handbook of Research on Technology Tools for real-world skill development. Information Science Reference.

Roy Winkelman is a 40+ year veteran teacher of students from every level kindergarten through graduate school. As the former Director of FCIT, he began the Center's focus on providing students with rich content collections from which to build their understanding. When not glued to his keyboard, Dr. Winkelman can usually be found puttering around his tomato garden in Pittsburgh.