This is the fifth and final post in a series on the characteristics of meaningful learning as used in the Technology Integration Matrix. The previous posts were Active Learning: Engaging Students’ Minds, Collaborative Learning: Building Knowledge in Community, Constructive Learning: Making Connections, and Authentic Learning: Mirroring the Real World.

The first thing that people notice about the Goal-Directed characteristic is that it’s at the “bottom” of the Technology Integration Matrix. The five characteristics of meaningful learning, however, are not presented in any sort of hierarchy. All of them are important and may receive more or less emphasis from one activity to another. The characteristics also overlap each other in significant ways. That’s why instead of always representing the five characteristics down the left side of the TIM grid, we sometimes present the characteristics in a circular format.

The simple explanation for the location of the Goal-Directed characteristic on the TIM is that it was the last characteristic we nailed down when creating the original Matrix long ago. There was a wide range of opinion among the various subject matter experts, teachers, tech supervisors, administrators, focus groups, and others we consulted. Some argued for an intentional characteristic. Others preferred self-directed or self-regulated. After much discussion we reached a consensus that referring to the fifth characteristic as Goal-Directed would make the TIM applicable to the widest range of instructional environments. Nearly two decades later, I agree that “Goal-Directed” was the best choice, although I’m still not satisfied that the name conveys all we intend for this characteristic. Far from being an afterthought relegated to the basement of the Technology Integration Matrix, Goal-Directed learning can be considered the capstone of the five TIM characteristics.

So what is Goal-Directed Learning?

The 2011 edition of Meaningful Learning with Technology introduces Goal-Directed learning in this manner.

All human behavior is goal directed. That is, everything that we do is to fulfill some goal. That goal may be simple, like satiating hunger or getting more comfortable, or it may be more complex, like developing new career skills or studying for a master’s degree. When learners are actively and willfully trying to achieve a cognitive goal, they think and learn more because they are fulfilling an intention. Technologies have traditionally been used to support teachers’ goals, but not those of learners. Technologies need to engage learners in articulating and representing their understanding, not the teachers’. When learners use technologies to represent their actions and construction, they understand more and are better able to use the knowledge that they have constructed in new situations. When learners use computers to do skillful planning for doing everyday tasks or constructing and executing a way to research a problem they want to solve, they are intentional and are learning meaningfully.

—Jane L. Howland, David H. Jonassen, Rose M. Marra

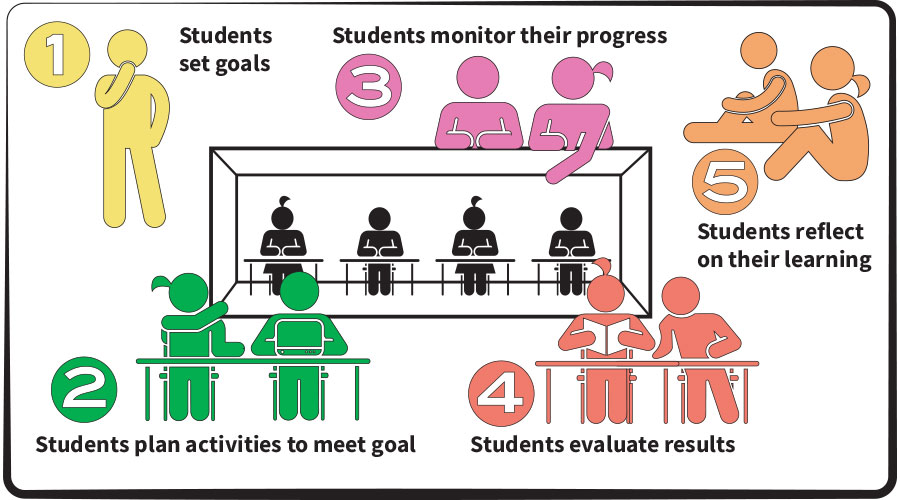

If you examine the descriptors within the TIM for the Goal-Directed characteristic, you’ll find that we have teased out five specific student activities that comprise Goal-Directed learning as presented in the TIM:

- Setting goals

- Planning activities

- Monitoring progress

- Evaluating results

- Reflecting upon learning

Identifying these five components creates a practical framework for thinking about and implementing Goal-Directed learning. Teachers can introduce the components in any order taking in consideration student readiness and curriculum flow. Students are more likely to understand terms like “planning activities” or “monitoring progress” than “Goal-Directed learning.” A school or district may choose to provide professional development broken out into these various topics. Or a teacher may decide just to focus a coaching cycle on a single component.

Identifying these five components also impacts classroom observations—especially when technology is leveraged to achieve the components. It’s one thing to say, “Ms. Smith has a very Goal-Directed classroom. Her students really think about their thinking.” And it’s another to say, “In Ms. Smith’s class I observed a group of students using an online project management tool to track their science experiment progress. I also observed several students who had completed their social studies unit reflecting upon what they learned in their journaling app.”

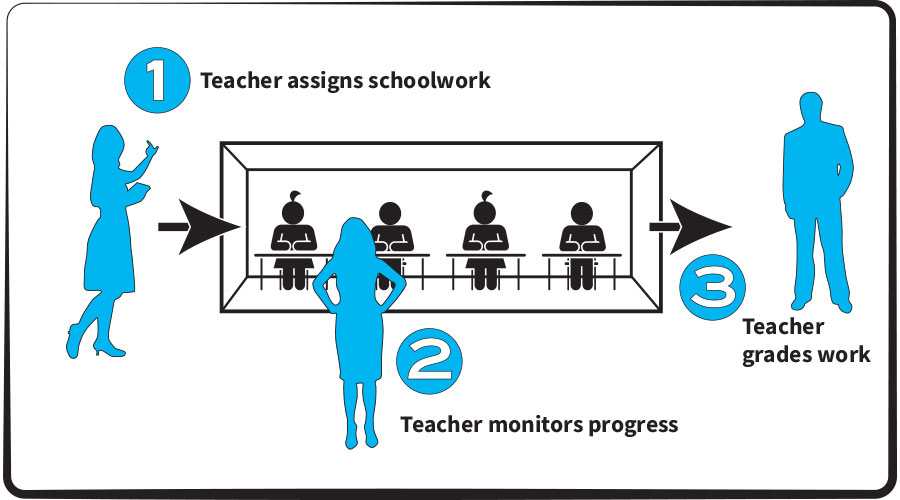

The Traditional “Schoolwork Box”

Sometimes a caricature of a practice can communicate an essential truth.

Generations of students were conditioned to expect a classroom to operate as though the students were sitting in a giant box. The teacher dropped an assignment into a slot at one end of the box and the students pushed their finished work out through a slot at the other end for the teacher to grade. The teacher kept an eye on the inner workings of the box to ensure the gears were turning properly and no one was dozing off or shooting spitballs. Decisions about the goals of an activity and evaluating it were always made in the world outside of the box—a world unknown and generally mysterious to students.

In this caricature of a traditional classroom, the teacher begins with a goal and plans a classroom activity. Alas, the students are likely unaware of the goal and so they don’t necessarily understand the larger picture of the various steps they’re told to do. Their focus for the project is usually narrowed down to a simple checklist (10 points for a title slide, 20 points for inserting a chart, 20 points for creating a bulleted list in the presentation, etc.). They know if they follow the steps and meet the requirements for their assignments, they’ll pass the course. That may be their only real goal. The students may have all manner of intentions bouncing around in their heads (pass a note, chat up the cute new student, get homework done in class), but any instructional intentionality exists outside of the schoolwork box in a higher realm inhabited only by teachers.

Escaping the “Schoolwork Box”

The Goal-Directed characteristic of the TIM is all about freeing students from the confines of the traditional schoolwork box. It’s a chance for them to enter the mystical realm outside the box that was previously reserved for teachers. From this new perspective, students have a grasp of the overall goal of an activity right from the start. They are involved in designing and planning the activities based on their knowledge of the goal. They learn to objectively monitor their own progress in light of the goal and of the activities they’ve planned. They are involved in the evaluation of the results and have opportunities to reflect upon their learning from a vantage point outside the schoolwork box. Metacognition happens!

Their schoolwork has become more meaningful for the students because they now understand the goals outside the box. Or, to put it more succinctly, their learning is now Goal-Directed.

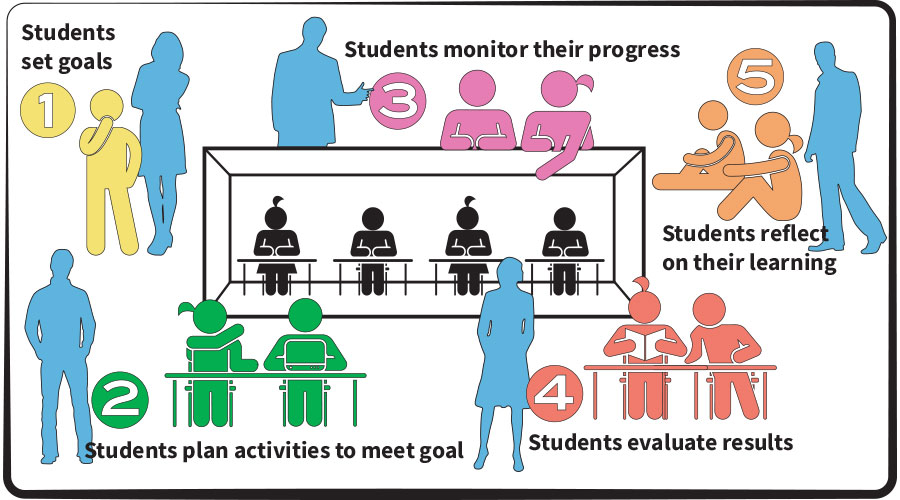

So, where’s the teacher?

Short answer: Everywhere!

The students weren’t empowered to participate in the world outside the box by accident. They learned the five Goal-Directed skills from a teacher who modeled those skills, gave students the tools to practice those skills, and invited the students to share a vantage point that gives meaning to their schoolwork.

The Technology Integration Matrix encourages a Goal-Directed learning environment by making use of the technology tools that support this type of thinking. At the Entry level, students are pretty much “in the box” all day. If technology is used for goal-setting, planning, monitoring, or evaluation, it’s most likely used by the teacher only. At the Adoption level, students begin to learn the mechanics of using technology tools in conventional ways. By the Adaptation level, the students start to use the tools independently and have opportunities to explore capabilities of the technology on their own. There are now clearly times in the school day when they are “out of the box” and thinking about their own thinking. By the Infusion level, the students regularly function out of the box. They have a rich variety of technology tools available to them and can select the tool or tools most appropriate to their goal-setting, planning, monitoring, evaluating, or reflecting needs. Finally, at the Transformation level the students engage in higher-order activity that would not have been possible without the assistance of technology.

And this brings us to the end of our exploration of the five characteristics of meaningful learning included in the Technology Integration Matrix. You can review any of the four previous posts by using the links below. If you have questions about the TIM or about using TIM Tools in your school or district, please don’t hesitate to contact us at TIM@FCIT.us.

Related Post

The TIM and Time Management

If you didn’t think teaching time management in school was an important skill, take five minutes to talk to any parent or grandparent who struggled with kids at home and “Zoom School” in the past year. Subtract the usual scaffolding of a physical classroom with wall charts, calendars….

Roy Winkelman is a 40+ year veteran teacher of students from every level kindergarten through graduate school. As the former Director of FCIT, he began the Center's focus on providing students with rich content collections from which to build their understanding. When not glued to his keyboard, Dr. Winkelman can usually be found puttering around his tomato garden in Pittsburgh.